Don't you LOVE Fellini's

La Strada?

Tell me you've seen La Strada. If you haven't, get to it and check back with me later.

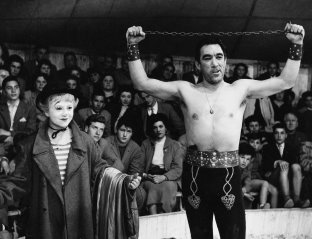

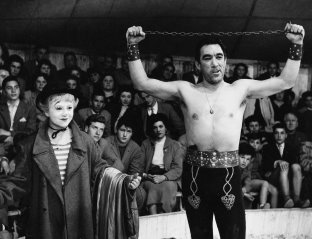

I just watched it again last night — for perhaps the fourth time. The first time you see it, what really hits you is Giulietta Masina's performance as the sweet, childlike Gelsomina.

She has one of the most disarming and memorable faces in film history. But the more times I watch this film, the more taken I am with Anthony Quinn's portrayal of the strong man, Zampano. And the more I realize that the movie isn't really about her, it's about

him.

Zampano is simply a brute — angry, violent, cruel, paranoid. He occasionally makes a show of being generous: giving gifts to Gelsomina's siblings (after

buying her away from them), or offering to assist a nun with her work (shortly before he

steals from her). His small attempts at graciousness are, for him, painfully out of character. But to those around him, they are practically invisible: a tip of the hat, a tentative handshake, a word of rehearsed politeness... and at the first tremor of uncertainty he retreats quickly into the comfort of his rage.

Whatever chance there is of Zampano being drawn out by Gelsomina's sweetness is completely destroyed when they cross paths with the Fool. For all the sweetness and warmth he demonstrates towards Gelsomina, the Fool is unable to stop hurling playful insults at Zampano, even when it becomes clear that he's talking himself into an early grave.

In that sense, the Fool is a perfect mirror of Zampano, as much a slave to wit as Zampano is a slave to anger. His ill-advised taunting of the brute becomes infuriating — we desperately want him to

shut the hell up, because we know only too well how it will end if he persists. And we care for his well-being not for his own sake, but because he brings Gelsomina so much joy.

But the more threatened the Fool becomes, the more relentlessly he ridicules Zampano. And when the inevitable finally happens, we mourn not the death of the Fool, but the devastating effect on Gelsomina. Her eyes glaze over with a sadness that will never leave her, and we realize (as does Zampano, ultimately) that although we have seen her bounce back from a thousand hurts, this time her heart has been broken beyond repair.

We can sense, especially toward the end of the film, that Zampano

wants to find nobility in himself. But nobility is beyond his nature. Zampano's most noble moment is a morally empty gesture — when he quietly abandons Gelsomina in the snowy mountains while she sleeps, he takes a moment to place her trumpet at her side.

Zampano never finds his nobility — years after abandoning Gelsomina, he seems sad and worn out, but he is largely unchanged. But finally, painfully, he faces the ugly truth of himself. He realizes at last the weight of his loss and the cruel limits of his humanity. He doesn't understand it, but he

sees it. In one of the most powerful endings in cinema, he can do nothing but lash out at everyone around him, then wander alone to the ocean, fall into the sand, and sob in anguish and remorse.

The truth of this film is, we are ALL Zampano — trapped within ourselves, yet still able to recognize our flaws and to understand the hurts we do to others. Who among us does

not aspire (secretly or openly) to be noble? To

some extent, we all seek out the “better angels” of our nature (some more than others, right Dick Cheney?). But in the end, we all are exactly what we are. We can learn and change and grow, but we remain always ourselves. Zampano cannot escape himself. Nor could the Fool. Nor can any of us. That is our shared curse.

Whatever chance there is of Zampano being drawn out by Gelsomina's sweetness is completely destroyed when they cross paths with the Fool. For all the sweetness and warmth he demonstrates towards Gelsomina, the Fool is unable to stop hurling playful insults at Zampano, even when it becomes clear that he's talking himself into an early grave.

Whatever chance there is of Zampano being drawn out by Gelsomina's sweetness is completely destroyed when they cross paths with the Fool. For all the sweetness and warmth he demonstrates towards Gelsomina, the Fool is unable to stop hurling playful insults at Zampano, even when it becomes clear that he's talking himself into an early grave.